- Home

- Nadia Bolz-Weber

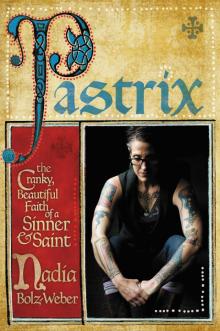

Pastrix Page 7

Pastrix Read online

Page 7

That first day, I walked around the surgical unit trying to figure out what the hell I was supposed to be doing. “Is there anything the chaplain’s office can do for you?” I asked an elderly woman recovering from shoulder surgery, expecting her to ask me to pray or bring her a Bible. Or possibly she had a prayer book covered in pictures of angels hidden in the drawer and from which I could read to her. “Oh that’s all nonsense, dear. I’m an atheist.” Before realizing I was saying it, I blurted out admiringly, “Man, good for you. I wish I could pull that off.”

During my next visit, to another elderly orthopedic patient, I again struggled to figure out what I was supposed to say, so instead I sat in the cheerful waterproof chair and watched Court TV with him. I had forgotten I was wearing a pager until it started buzzing, causing me to miss the Court TV ruling. It was the ER.

There were a couple things I didn’t know that just moments before had not been an issue for me: Would Tyra get her cleaning deposit back from her pockmarked landlord? And where is the ER?

“I was paged?” I said to the security guard at the ER desk. She offered me a sarcastic “congratulations” look and went back to her crossword.

“Uh, I’m from the chaplain’s office?” I said. She pointed to a door that said NO ADMITTANCE and then looked at me like I was an idiot. Apparently my name badge allowed me to go through doors like that.

I finally found a nurse who would make eye contact with me. I said I was paged, but that I wasn’t sure what for.

“Trauma one,” she said.

Inside the trauma room, a nurse was cutting the clothes off a motionless man in his fifties on a table; tubes were coming out of his mouth and arms. Doctors started doing things to him not meant for my eyes and sorely misrepresented on TV shows. Another nurse was hooking things up to him while a doctor put on gloves and motioned for paddles, which he then placed into the motionless man’s freshly cracked–open chest.

A nurse stepped back to where I was standing, and I leaned over to her. “Everyone seems to have a job, but what am I doing here?”

She looked at my badge and said, “Your job is to be aware of God’s presence in the room while we do our jobs.”

For the rest of those two-and-a-half months I often found myself in the ER trauma room watching life going in and out of the patients on the table—the doctors and nurses violently attempting to resuscitate them. And in that messy chaos, my job was to just stand there and be aware of God’s presence in the room. Kind of a weird job description, but there it was, and in those moments, I felt strangely qualified. I didn’t have the slightest idea what to say to someone who just had shoulder surgery, but I couldn’t help but feel God’s presence in the trauma room.

It wasn’t long before I found myself sensing God’s presence in other rooms, too. I felt it in the little white room with just enough space for four love seats and as many boxes of tissue where we brought the families of those who are dead, or might be dead, or should be dead, or had died and are now not dead, but we don’t know for how long. I’d sit with people in their loss. Their sixty-year-old father has just died. Their spouse of thirty-one years has just experienced a brain aneurism. Their sister has just swallowed four bottles of pills and they are waiting to hear if her body is dead or just her brain. In this little white pit of pain, I was the chaplain.

I noticed that the family and friends of those who had unexpectedly died, in a grief so thick it sucked the oxygen out of the room, would gaze off and say, “Just this morning we were eating breakfast and talking about baseball,” or “We were just walking the dog, laughing about the kids.”

The life changing seems always bracketed by the mundane. The quotidian wrapped around the profound, like plain brown paper concealing the emotional version of an improvised explosive devise. Then, in a single interminable moment, when we discover the bomb, absolutely everything changes. But when we recall it from our now forever–changed lives, when we start with the plain brown wrapping, it looks like every other package, every other morning, every other walk.

The Tuesday of Holy Week, I was sitting in the windowless chaplain’s office filling in my paperwork when the ER paged me. I had just remembered that my kids’ Easter baskets would be empty on Sunday if I didn’t remember to stop by Target in the next couple days.

When I got to the ER, things felt different. Quiet.

On the table was a thirty-one-year-old DOA. She was killed when she stepped out of her car on the highway. Her two-year-old and five-year-old sons were in the minivan. “They are unhurt, and we need you to stay with them until other family can arrive,” I was instructed.

They were unhurt. Right.

I took the boys hand in hand to pediatrics, where there are toys and TVs. We found some trucks to play with on the floor, and as I scooted a red fire engine back and forth over the cheerful linoleum, I was aware that for the rest of these boys’ lives, this would be the day their mom died. This would be the day they sat scared and crying in a minivan until the police arrived. This would be the day that their mom was taken from them before they could really even know who she was and before she could love them into adulthood. I’m not sure what else I could have given them but juice boxes and my time. Two hours later, when their extended family showed up, I almost offered to buy their Easter baskets.

I was the chaplain, but I didn’t have answers for anyone. I’d bring people water, make some calls for them, keep bugging the doctors to provide more information, but words of wisdom I had none. I just felt the unfairness of it all. I felt the uncontrollable terror of loss, the finality of someone never having a father again. I felt a sadness that is both poetic and grotesque. I would stand by and witness the disfiguring emotional process we politely call grief and, yes, I was aware of God’s presence, but I wanted to slap the hell out of him or her or it.

After all, maybe if God sensed that I wasn’t a girl to fuck with, then my loved ones would be spared. I couldn’t stop thinking about my own husband and children. Harper and Judah were small at the time, and I needed them to be able to live in a world where their mom might not just die outside a minivan on a Tuesday in Holy Week. And sometimes, before I could stop myself, I’d think what if that were Matthew on the table? And then I’d get angry, that defensive kind of angry. The kind of angry that keeps the fear from embarrassing you. Or taking over.

You hear a lot of nonsense in hospitals and funeral homes. God had a plan, we just don’t know what it is. Maybe God took your daughter because He needs another angel in heaven. But when I’ve experienced loss and felt so much pain that it feels like nothing else ever existed, the last thing I need is a well-meaning but vapid person saying that when God closes a door he opens a window. It makes me want to ask where exactly that window is so I can push him the fuck out of it.

But this is the nonsense spawned from bad religion. And usually when you are grieving and someone says something so senselessly optimistic to you, it’s about them. Either they want to feel like they can say something helpful, or they simply cannot allow themselves to entertain the finality and pain of death, so instead they turn it into a Precious Moments greeting card. I’ve both had those things said to me and have been the one to say them. But as a chaplain, I felt that people really just needed me to mostly shut the hell up and deal with the reality of how painful it all is.

When I first began dipping my toe back into the waters of Christianity, back when Matthew and I were dating, I read a lot. Mostly I read Marcus Borg and others who had done work on what is called the Historical Jesus. Matthew had given me a book called Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. It was my gateway drug. Unlike what I saw as the irrational faith of my fundamentalist upbringing, these people were scholarly and reasonable and searched for what we could really know about the man Jesus of Nazareth. He was a Palestinian Jew in the first century who garnered a following based on his charisma and teaching. Man, was he a great guy, really in touch with his God consciousness. I loved these people for rescuing the ima

ge of Christ from the bondage of ignorance and the religious right, and I felt high on meeting Jesus again for what really did feel like the first time.

This was the bonus to liberal Christianity: I could use my reason and believe at the same time. But it only worked for me for a short while. And soon I wanted to experiment with the harder stuff. Admiring Jesus, while a noble pursuit, doesn’t show me where God is to be found when we suffer the death of a loved one or a terrifying cancer diagnosis or when our child is hurt. Admiring and trying to imitate a guy who was really in touch with God just doesn’t seem to bridge the distance between me and the Almighty in ways that help me understand where the hell God is when we are suffering.

And of course I didn’t get much help in childhood. The image of God I was raised with was this: God is an angry bastard with a killer surveillance system who had to send his little boy (and he only had one) to suffer and die because I was bad. But the good news was that if I believed this story and then tried really hard to be good, when I died I would go to heaven, where I would live in a golden gated community with God and all the other people who believed and did the same things as I did. (When I was estranged from my conservative Christian parents, I used to joke that my mom would say, in her slight Kentucky accent, “Nadia, the least you could do is come visit us more often, since we won’t be spending eternity together.” I wondered if my parents understood that spending eternity with them and their friends is not exactly their church’s best selling point.) And anyway, this type of thinking portrays God as just as mean and selfish as we are, which feels like it has a lot more to do with our own greed and spite than it has to do with God.

The choir at Matthew’s church sang that Good Friday—three days after I had sat with two small, motherless boys on a hospital floor. I sat in the back pew and listened to the beautiful Latin and ancient melody coming from the voices of the people before me. When the reading of the passion began—the account in John’s Gospel of the betrayal, suffering, and death of Jesus—I listened with changed ears. I listened with the ears of someone who didn’t just admire and want to imitate Jesus, but had felt him present in the room where two motherless boys played on the floor.

I was stunned that Good Friday by this familiar but foreign story of Jesus’ last hours, and I realized that in Jesus, God had come to dwell with us and share our human story. Even the parts of our human story that are the most painful. God was not sitting in heaven looking down at Jesus’ life and death and cruelly allowing his son to suffer. God was not looking down on the cross. God was hanging from the cross. God had entered our pain and loss and death so deeply and took all of it into God’s own self so that we might know who God really is. Maybe the Good Friday story is about how God would rather die than be in our sin-accounting business anymore.

The passion reading ended, and suddenly I was aware that God isn’t feeling smug about the whole thing. God is not distant at the cross and God is not distant in the grief of the newly motherless at the hospital; but instead, God is there in the messy mascara-streaked middle of it, feeling as shitty as the rest of us. There simply is no knowable answer to the question of why there is suffering. But there is meaning. And for me that meaning ended up being related to Jesus—Emmanuel—which means “God with us.” We want to go to God for answers, but sometimes what we get is God’s presence.

CHAPTER 9

Eunuchs and Hermaphrodites

As they were going along the road, they came to some water; and the eunuch said, Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?

—Acts 8:36

The 1980s pop star Tiffany has a hermaphrodite1 obsessive who once helped me write a sermon. Kelly, the hermaphrodite in question, doesn’t know that she helped me write a sermon. All she did was walk into the same coffee shop in Denver where I was at that moment struggling to write a sermon for my fledgling new church about Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch. We Lutherans, as well as most Catholics, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Episcopalians, use the same set of assigned texts to preach from each Sunday. It’s called the Revised Common Lectionary. The passage on the Ethiopian eunuch was the assigned text for that week, and although using the assigned texts is an expectation, not a law, I’ve just never trusted myself enough to go off reservation. The last thing my people need is for me to start deciding what verses to preach from each Sunday. I’d give it three months before that turned into a Heart of Darkness situation.

When I saw Kelly, I first felt shock, followed quickly by revulsion: shock because I had seen a documentary about her just two days before (I Think We’re Alone Now—about her and another Tiffany-obsessed fan, a fifty-year-old man with Asperger’s); revulsion at how both male and female she seemed. She wasn’t cool androgynous like David Bowie or Annie Lennox. Kelly had long hair like a woman, a face that seemed both female and male, breasts, and a man’s midsection and thick legs.

Then I experienced shame. I was ashamed of feeling repulsed. I’ve been around gay men and queer gals and transgender folks most of my life and yet I felt disgusted by this intersex person in front of me.

Watching documentaries about intersex celebrity obsessives usually doesn’t fit neatly into my workweek, but I had been doing some research about eunuchs for a sermon, and the black hole of the Internet sucked me into watching I Think We’re Alone Now. And then Kelly walked into the coffee shop I frequented. She was with another woman, and they both ordered drinks to go. I sat there stunned, half expecting Tina Fey to walk in next; I had, after all, watched 30 Rock the night before.

Fey never showed, and I still had no sermon about the eunuch from Ethiopia. I had words on paper, but they were stupid.

The story of the Ethiopian eunuch comes from the book of Acts. After Jesus had risen from the dead, messed with everyone’s heads, grilled them all a fish breakfast on the beach, and had a few more choice meals, he then ascended into heaven. But not before telling his followers to tell the story about him to all peoples and baptizing them in the name of the Trinity.

The first gentile convert ended up being a black sexual minority. The story goes that the Spirit told Philip to go to this certain desert road. There he found a eunuch in a chariot who was reading from the scroll of Isaiah. Philip climbs in the chariot and tells this castrated man from Ethiopia about Jesus, at which point the eunuch says, “Look over there! There is water. What keeps me from being baptized?” Philip baptizes him and then vanishes.

Growing up I always heard this story called “The Conversion of the Ethiopian Eunuch.” I was always told that the message of this text was that we should tell everyone we meet about Jesus because in doing so we might save them. We might convert them. We might change them into being us so they, too, can live in a mansion in heaven, but of course probably not one as nice as ours. But reading it now I found that it’s all such great material for liberal Christians. I mean, come on. The first gentile convert to Christianity is a foreigner, who is also a person of color and a sexual minority? If only the guy were also “differently abled” and gluten intolerant.

So, the day I saw Kelly the hermaphrodite in a Denver coffee shop, I had already written the first draft of a slightly self-congratulatory sermon on inclusion in which I took a couple potshots at Christians who aren’t as “open and affirming” of the GLBTQ community as we are at House for All Sinners and Saints. We have lots of queer folk. Of course we’re still 95 percent white, but that’s not the point. We understand the Gospel. Others don’t.

As you know, Lutherans had been fighting about the issue of human sexuality for years at this point. This whole argument my denomination was having around including “the gays” mirrored the argument forty years earlier around the ordination of women, which mirrored the argument in the early church around inclusion of gentiles. Which means that disagreements over “inclusion” happened approximately twenty minutes after Christianity started.

Much like the early church, who were convinced that gentiles could become Christians only if they changed i

nto being Jews first (which, as we know, involved a rather unpleasant process for the fellas), a segment of the church today thinks that if we extend the roof of the tent to include the gays, then the whole thing could come crashing down around us. The tent of the church must be protected from being stretched too thin and collapsing in on itself. Some “protectors of the tent” suggest that we must “evangelize” the gays, i.e., change them into us.

Several organizations exist to help queer folks “pray away the gay”; that is to say, sexual minorities can become part of more conservative churches if they just become straight first (which, obviously, doesn’t work). Meanwhile, the other side of the church, the liberal side, is all about “inclusion”; we see ourselves as the “extenders of the tent” and must stretch the tent to include the marginalized, the less fortunate, the minorities. Our job is to extend the tent until everyone fits because we believe in inclusion. And this was the point of the mediocre sermon I wrote about the Ethiopian eunuch.

And yet, there I was, now a pastor of a GLBTQ “inclusive” congregation, and I felt revulsion at seeing an intersex person. It was humbling to say the least. And it made me face, in a very real way, the limitations of inclusion. If the quality of my Christianity lies in my ability to be more inclusive than the next pastor, things get tricky because I will always, always encounter people—intersex people, Republicans, criminals, Ann Coulter, etc.—whom I don’t want in the tent with me. Always. I only really want to be inclusive of some kinds of people and not of others.

After Kelly left the shop, I thought about something that happened a few weeks earlier. Stuart, the gay leader at our church who had coined “thanks, ELCA!,” had shown up to liturgy wearing slacks and button-down shirt rather than his normal ironic grease monkey jacket and jeans. I like to call Stuart a “dos equis,” an ex-ex-gay.

Pastrix

Pastrix